National Cemetery Administration

History of the 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument

Prepared by Alec Bennett, NCA Historian

Introduction

The Civil War was a seminal event in American History; its importance can hardly be overstated. Over four years, approximately 620,000 soldiers were killed in the conflict - 360,000 from the Union and 260,000 from the Confederacy - or 1.8 percent of the total U.S. population. Fourteen percent of the total population of all military personnel was killed. One hundred fifty years later, the Civil War still remains the bloodiest conflict in American History.

The sheer number of lives lost naturally resulted in an outpouring of commemorative efforts, to provide the country an opportunity for reflection, and to honor the fallen soldiers. Americans commemorated the Civil War soldier dead through Memorial Day ceremonies, and by erecting monuments in stone and metal on battlefields, in cemeteries, around state and local government buildings, and in public parks.

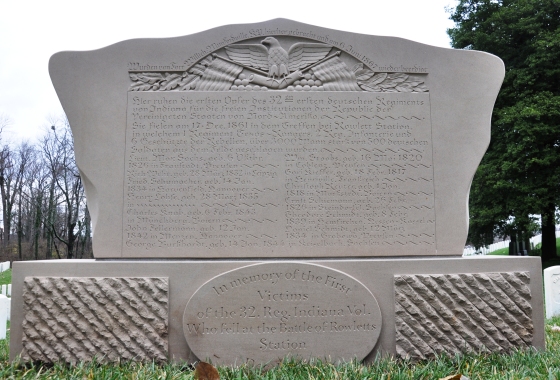

The 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument was carved in January 1862 after the Battle of Rowlett's Station in Munfordville, Kentucky. It is believed to be the oldest extant Civil War monument. Private August Bloedner carved the monument to mark the interments of fellow soldiers in the 32nd Indiana Infantry, a regiment entirely comprised of German-Americans who fell in the battle. It was originally installed on the battlefield. In 1867, the 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument was moved to Cave Hill National Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky, along with the remains of 11 of the 13 soldiers whose names are inscribed on the monument. After being reinterred in the cemetery, the 11 soldiers received individual markers, causing the carving to shift in meaning from a headstone marking the remains of multiple soldiers, to a monument commemorating their sacrifice.

32nd Indiana Infantry Monument, 2004, Cave Hill National Cemetery, before removal for conservation.

32nd Indiana Infantry Monument, 2004, Cave Hill National Cemetery, before removal for conservation.

August Bloedner carved the monument from St. Genevieve limestone, a type of Indiana limestone that is soft, porous, and no longer used for sculpture or building purposes. By the 1950s, the monument was beginning to spall. By the early 2000s, approximately 50 percent of the inscription was lost. To preserve what was left of the monument, on December 17, 2008 (the 147th anniversary of the Battle of Rowlett's Station), the National Cemetery Administration, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, removed it to an indoor storage facility at the University of Louisville, where it received professional conservation.

On August 18, 2010, NCA moved the 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument to its new home at the Frazier History Museum, in downtown Louisville. The monument is on display in the museum foyer, free of charge to the public.

To continue to honor the soldiers from the 32nd Indiana Infantry buried in Cave Hill National Cemetery, NCA commissioned a new, successor monument to be installed in the location of the original. This was an exacting task. NCA wanted to clearly represent the successor as a modern piece, while simultaneously establishing a strong visual connection with the original.

After reviewing three candidates, NCA commissioned stone carver Nicholas Benson of The John Stevens Shop, Newport, Rhode Island, to hand-carve a successor monument. Benson is a third-generation master of hand letter carving, and completed the inscriptions on the Martin Luther King Jr. and World War II memorials.

Front of successor 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument in Cave Hill National Cemetery, 2011.

Front of successor 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument in Cave Hill National Cemetery, 2011.

The John Stevens Shop produced the replacement monument based upon a 1955 photograph and period German-language newspaper articles; it was installed in September 2011. Though it was created from a more durable Indiana limestone, the replacement monument is the same size and form and features the same German inscription as the original. The back of the replacement monument is inscribed with an English translation.

NCA dedicated the new successor monument on December 16, 2011, almost 150 years to the day of the Battle of Rowlett's Station. Decedents of the 32nd Indiana Infantry laid a wreath on the monument to honor their ancestors.

Kentucky in the Civil War

The states along the border between the Union and Confederacy, including Maryland, Missouri, and especially Kentucky, were vitally important to either side. At the outbreak of war, President Abraham Lincoln is reported to have said, "I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky."

The state of Kentucky had long served the role as a mediator between the North and South. Henry Clay, legendary senator from the state, helped broker the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850, both of which attempted to diffuse the contentious political issue of the expansion of slavery into new states and territories. In the years leading up to the Civil War, Kentucky was bordered by six states, three slave and three free. It was a slave state that nonetheless opposed secession.

However, after the outbreak of war, Kentucky did not initially ally with the Union. In May 1861, a month after the firing on Fort Sumter, the legislature passed, and the Governor signed, a resolution affirming the state's neutrality in the war. This ineffectual measure did little to stop it from being drawn into the conflict. Both sides recruited Kentucky citizens from across state borders. By September 1861, both the Union and the Confederacy effectively circumvented the state's announced neutrality by establishing fortifications in Kentucky.

Detail from the map, "Campaigns of the Civil War in the West" by A.B. Adlerman, ca. 1910, showing the location of the Battle of Rowlett's Station. (Library of Congress)

Detail from the map, "Campaigns of the Civil War in the West" by A.B. Adlerman, ca. 1910, showing the location of the Battle of Rowlett's Station. (Library of Congress)

That same month the Kentucky legislature, overriding a veto by the Governor, passed a resolution demanding an immediate withdrawal of all Confederate troops. With this motion, the state officially aligned itself with the Union.

Reflective of the state's divided loyalties, soldiers from Kentucky enlisted about evenly in the Union and Confederate armed forces. As is frequently noted by historians, both President Abraham Lincoln and President Jefferson Davis of the Confederacy were born in Kentucky, about 100 miles away from each other. Moreover, four of the brothers of the Kentucky-born First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln fought for the Confederacy.

During the war, Kentucky did not experience the same level of carnage as in neighboring Tennessee and Virginia. After a series of minor clashes in late 1861, including the Battle of Rowlett's Station, the Union victory at Mill Springs on January 19, 1862, halted an early Confederate offensive into the state. The following month, Union forces invaded Tennessee and successfully captured the Confederate forts Henry and Donelson. The fall of these forts forced many of the remaining rebel troops in Kentucky to abandon their positions and head south, to help bolster the Confederate military presence in Tennessee. By June, all major Confederate forces had withdrawn from Kentucky.

In August the Confederate Army once again advanced into Kentucky in an attempt to draw the state into the Confederacy. The Kentucky Campaign culminated in the Battle of Perryville on October 8, 1862. The Union victory there again forced the Confederates to retreat back into Tennessee, and the Confederate Army did not mount another large-scale invasion of Kentucky for the rest of the war. Confederates continued to engage in raids and small guerilla actions in the state, but there no further substantial engagements.

Despite the relative lack of bloodshed in Kentucky, the state was strategically vital to the Union Army as its northern border, the Ohio River, served as a conduit for soldiers and supplies. Moreover, two of the river's tributaries, the Cumberland and the Tennessee rivers, stretched across Kentucky into Tennessee. During the war, Union forces used both of these waterways to advance into the heart of the Confederacy.

There are six Civil War-era national cemeteries in Kentucky, more than any other state except Virginia. The large number of small cemeteries here was an early outcome of two factors, as reported by Captain Edmund Whitman, who oversaw the Department of the Tennessee. "Collecting the dead into larger groups…cannot be so fully realized throughout Kentucky, as in the other states," he wrote to his commander in 1866, "not only from the very seated condition of the graves, but from the nature of the country itself, a large portion of it without railroads and with its surface broken by mountain ridges." These cemeteries were associated with local military camps and hospitals, such as Camp Nelson or Lexington national cemeteries, or with a local battle, as is the case with Mill Springs National Cemetery.

German Immigration before the Civil War

In the two decades before the Civil War, there was a surge of immigration into the United States from Ireland, Germany, and Great Britain. In particular, from 1845–1854 nearly 3 million new arrivals came to America in what was the largest wave of immigration in American History up to that time. On the whole, these new immigrants were much poorer and a higher percentage was Roman Catholic, compared to previous waves of immigrants. They came during a period of sustained economic growth in the United States, while many European nations were enduring political and economic turmoil.

Approximately 1.5 million Germans immigrated to the United States during this surge. The vast majority came in search of economic opportunities, although a small minority came for political reasons. In 1848, Germany was a loose confederation of states dominated by the noble classes, without a democratically elected, representative government. Rebelling against this status quo, reformers sparked a series of revolutions in the different states, advocating for a unified Germany and increased democratic reforms. When the forces of the noble classes defeated the revolutions, many of the reformers fled to the United States. Often, these "Forty-Eighters" became political and economic leaders of the German communities in America.

In general, many German immigrants who came to the United States in the mid-19th century tended to settle in the interior of the country, in the Midwest and the Ohio River valley. Following this trend, both Louisville and Cincinnati, Ohio, were popular destinations. By the mid-1850s both Louisville and Cincinnati had multiple German-language newspapers. In 1855, immigrants comprised a quarter of Louisville's population of 43,000. In Cincinnati, many Germans settled in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood, whose name still reflects their influence. Indianapolis' German population was not as large, and immigrants were more dispersed across the state.

Nationwide, the waves of immigration during the mid-19th century led to a political backlash, culminating in the formation and swift rise of the Know-Nothing Party, which won a series of state elections in 1854 on an anti-immigration, anti-Catholic platform. The party won the governorship and the state legislature in Massachusetts, and won control of the Maryland and Tennessee state legislatures. The next year the party won governorships in New Hampshire, Connecticut and Rhode Island.

Anti-immigrant sentiment erupted in violence during a primary election in Louisville on August 6, 1855, in which a mob threatened and intimidated the local immigrant population away from the polls. Rioting ensued, and at least 22 were killed. While nothing on the same scale occurred in Cincinnati, there was tension between the non-immigrant population and the new immigrants. The rise in the Irish and German population of Cincinnati coincided with an increase in crime, which local newspapers attributed to the recent immigrants.

After victories at the polls in 1854 and 1855, the Know-Nothing Party renamed itself the American Party, and nominated former President Millard Fillmore as its candidate in the 1856 presidential election. Fillmore won one state - Maryland - but soon after the party was effectively finished on the national stage. The Dred Scott decision of 1857 and the clashes of Bleeding Kansas divided the American Party over the issue of slavery.

At the advent of the Civil War, the immigrant population of the Northern states was much greater than the South, as cities in the North were more industrialized and offered more job opportunities to the new arrivals. While there was a small German community in Texas and other Southern states, in general there were few jobs available for immigrant labor in the South. According to the 1860 census, approximately 90 percent of the nation's immigrant population lived in the North. On the whole, the German community largely opposed slavery and strongly supported the Republican Party, and overwhelmingly enlisted in Union companies. Over the course of the war, an estimated 200,000 native Germans served, composing nearly 10 percent of the Union Army and Navy. Thus, while European immigrants contributed to the war efforts of both the blue and the gray, they enlisted in the Union ranks in much greater numbers.

32nd Indiana Infantry

On the whole, most native Germans joined military units with American-born volunteers. However, some states with large German populations formed companies consisting entirely of German-American soldiers. This includes the 9th Ohio Infantry, 74th Pennsylvania Infantry, 9th Wisconsin Infantry, and 32nd Indiana Infantry.

The 32nd Indiana Infantry consisted of German immigrants throughout the state, and from just across the state border in Cincinnati. Organized in Indianapolis during summer 1861, the 32nd Indiana Infantry marched to Kentucky that fall, joining the Army of the Ohio. It was also known colloquially as the "First German" Indiana regiment because it was entirely made up of German-Americans, many of whom were not fluent in English. At the start of the war, the 32nd Indiana consisted of 937 soldiers, a typical number for Civil War regiments.

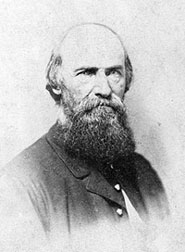

The commanding officer of the regiment, Colonel August Willich, was personally selected by the Governor of Indiana, Oliver Morton. Col. Willich served as an officer during the German Revolutions of 1848, fighting on the side of the reformers. He immigrated to the United States in the early 1850s, and by 1858 was the editor of the Cincinnati Republikaner, a German-language newspaper.

Col. August Willich, ca 1865. (Library of Congress.)

Col. August Willich, ca 1865. (Library of Congress.)

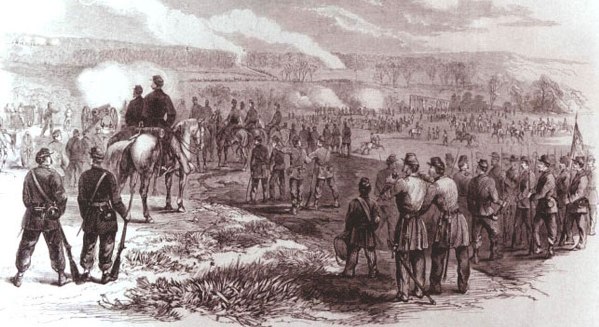

The Battle of Rowlett's Station

The Battle of Rowlett's Station was fought on December 17, 1861, between the 32nd Indiana Infantry and Confederate forces consisting of Terry's Texas Rangers, the 7th Texas Cavalry and the 1st Arkansas Battalion. Approximately 70 miles south of Louisville, Union forces were charged with protecting a pontoon bridge over the Green River to ensure the passage of soldiers and supplies along the Louisville & Nashville Railroad. When the Union forces encountered Confederate troops in the woods just south of Woodsonville, the two sides exchanged fire before withdrawing from the field.

The battle was small in scope, with 40 Union and 91 Confederate casualties, and the results were indecisive. Union forces did secure the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, allowing troops and supplies to continue to move through the area.

In Kentucky, the Battle of Rowlett's Station was soon overshadowed in importance by the Union victory at the nearby Battle of Mill Springs on January 19, 1862, which halted the Confederate advance into the state, and led to the Union campaign into Tennessee in February.

The Battle of Rowlett's Station was the first action for the 32nd Indiana Infantry. After bivouacking near Munfordville on February 10, the regiment moved toward Nashville and went on to fight in the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862.

The Battle of Rowlett's Station. (Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, January 18, 1862)

The Battle of Rowlett's Station. (Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, January 18, 1862)

Over the course of the war, the regiment fought in other large battles, including Chickamauga, Resaca, and the Siege of Corinth. The 32nd Indiana Infantry was mustered out in San Antonio, Texas in December 1865.

32nd Indiana Infantry Monument

August Bloedner was born in 1827 at Altenburg in the Duchy of Saxe-Altenburg (currently the state of Thuringia), Germany. From 1841-45, he attended the local Arts and Crafts School. In 1845, he left Altenburg for Dresden, entering the highly respected Royal Academy of Fine Arts, but soon after he withdrew before completing his studies. Bloedner came to the United States in 1849, and may have lived in New York City for a time, before settling in Cincinnati. He married Henrietta Behnke in 1856. After the outbreak of the Civil War, Bloedner enlisted in the Union Army on August 24, 1861, in Indianapolis for three years as a private, and was assigned to the 32nd Indiana Infantry Regiment.

After the Battle of Rowlett's Station, Bloedner and the 32nd Indiana Infantry bivouacked near Munfordville for approximately two months. During this time, Bloedner carved the 32nd Indiana Monument, and it was installed on the battlefield in late January 1862, marking the remains of those who fell. A fence was installed around the burial site and the monument.

The 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument is carved from St. Genevieve limestone, probably a local outcrop. It is approximately 60" wide by 49" high by 16" deep. In relief, there is a carved image of an eagle with its wings outstretched, clutching in its talons two cannons, which are resting on cannonballs. The eagle is flanked by American flags, along with an olive sprig and an oak branch. Below the relief panel, the monument is inscribed in a fraktur-like script in German with a brief description of the battle, and the names, birth dates, and birthplaces of those who fell. The translated inscription reads:

Here lie men of the 32nd First German Indiana Regiment sacrificed for the free Institutions of the Republic of the United States of North America.

They fell on 17 Dec. 1861, in an Encounter at Rowlett Station, in which 1 Regiment of Texas Rangers, 2 Regiments of Infantry, and 6 Rebel Cannons, in all over 3000 Men, were defeated by 500 German Soldiers.

Lieut. Max Sachs, born 6 Oct. 1826 in Fraustadt, Prussia

Rich Wehe, born 28 March 1832 in Leipzig

Fried. Schumacher, born 14 Jan. 1834 in Harvenfeld, Hannover

Henry Lohse, born 28 March 1835 in (unreadable)

Charles Knab, born 6 Feb. 1843 in Münchberg, Bavaria

John Fellermann, born 12 Jan. 1842 in Menzen, Hannover

Wm. Staabs, born 16 May 1820 in Coblenz, Prussia

Gari Kieffer, born 18 Feb. 1817 in Henriville, France

Christoph Reuter, born 1 Jan. 1818 in Markstedt, Bavaria

Ernst Schiemann, born 26 Feb. 1826 in Steindorfel, Saxony

Theodore Schmidt, born 8 Feb. 1839 in Hemkirchen, Hessen-Kassel

Daniel Schmidt, born 12 March 1834, in Grabowa, Prussia

George Burkhardt, born 14 Jan. 1844 in Keiselbach, Saxony

Of the 13 names inscribed on the monument, the remains of 11 were buried locally and marked by the 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument. The remains of the other two soldiers were sent to private cemeteries in Cincinnati for burial. Pvt. Max Sachs was buried in Adath Israel Cemetery (now part of Price Hill Cemetery) and Pvt. Theodore Schmidt was buried in Spring Grove Cemetery.

The 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument likely was originally intended to serve as a grave marker. Little is known about those soldiers who fell in the battle. 11 were privates, two were officers. According to the inscription on the monument, all were born in Germany, save for Carl Keiffer who was born in the Lorraine region of France on the German border. Their ages ranged between 18 to 43, which was typical for the Army; it is estimated that most Union soldiers were between the ages of 18 and 39.

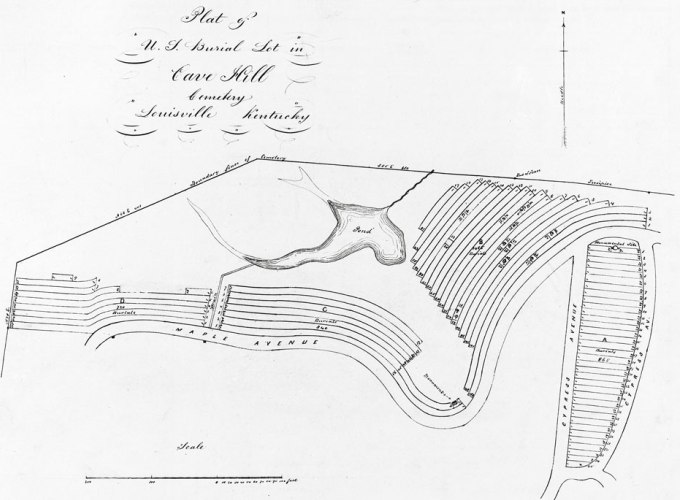

After the Civil War, the Office of the Quartermaster General (OQMG) of the U.S. Army was responsible for administering a nationwide reburial program to identify the burial locations of fallen Union Soldiers, and if necessary to reinter their remains into the new national cemeteries. In 1867, the OQMG moved the remains of the 11 soldiers buried on the Rowlett's Station battlefield and the 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument to Cave Hill National Cemetery in Louisville. Cave Hill National Cemetery is imbedded in a corner of the private Cave Hill Cemetery, a premier Rural-style burial ground established in 1848. The first interments in Cave Hill National Cemetery occurred in November 1861.

Drawing of Cave Hill National Cemetery from the "Report of Lt. Col. E.B. Whitman, Superintendent of National Cemeteries, Dept. of the Cumberland, 1869." The monument is labeled. (National Archives and Records Administration)

Drawing of Cave Hill National Cemetery from the "Report of Lt. Col. E.B. Whitman, Superintendent of National Cemeteries, Dept. of the Cumberland, 1869." The monument is labeled. (National Archives and Records Administration)

When the monument was moved to Cave Hill National Cemetery, it was installed on a base of Bedford limestone, with an English inscription that reads: "In memory of the first victims of the 32nd Reg. Indiana Vol. who fell at the Battle of Rowlett's Station, December 17, 1861." At this time, a German inscription was carved above the frieze, reading: "Brought here from Fort Willich, Munfordville, KY and reinterred on 6 June 1867."

Bloedner stayed with the 32nd Indiana Infantry throughout 1862. He was promoted to sergeant in January 1863, and was wounded on September 20 of that year in the Battle of Chickamauga. In October 1863 he was promoted to first sergeant; he mustered out on September 7, 1864, after completing a three-year enlistment. He returned to Cincinnati and worked as a stone cutter, before he died of heart disease on November 17, 1872, at age 46.

Civil War Monuments and Commemoration

Carved in late January 1862, the 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument is one of a small number of military monuments or memorials erected as the war was still raging. This is unsurprising, as the immediate energies of both sides were directed toward winning the conflict. Civil War monuments were erected more frequently after the war, as the attention of the country turned toward honoring the fallen soldiers, and as the population of Civil War veterans aged and reflected on their military service.

During the war, the Union was faced with the fundamental responsibility of burying thousands of fallen soldiers - a huge logistical challenge. In response to this need, Congress passed legislation in July 1862 enabling the president to establish national cemeteries for burial of the soldier dead. The Army covered the expenses for officer's remains to be sent back to their families. Over the course of the war, the federal government established national cemeteries near large concentrations of dead, including major battlefields, hospitals, and military installations. In many areas the dead were buried in private cemeteries. In the field, commanding officers were responsible for the burial of the men under their command. The exigencies of war meant that thousands of soldiers who fell in rural, remote areas were buried in isolated graves outside of cemeteries. Often, the identities of these soldiers were lost, their remains eventually marked with unknown headstones.

When August Bloedner carved the 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument it originally served as a headstone to mark the remains of the soldiers who fell. It would be another seven months before Congress passed legislation authorizing the acquisition of land for burial purposes, and the design of permanent government-issued headstones to mark the remains of soldiers was not established until 1873.

The Confederate States of America faced the same fundamental need to bury their dead. Similar to their northern foes, Confederate Army officers were responsible for burying the troops under their command. Burial grounds were created near hospitals; those who fell in battle, or in rural areas, were often buried outside of established cemeteries. The major difference between the burial policies of the two sides was that the Confederate government did not establish a system of cemeteries equivalent to national cemeteries in the North.

One of the first Confederate monuments - and likely the first erected to either side - was the original Francis Bartow Monument on the battlefield of First Manassas in Virginia. The marble column, approximately 6 feet tall based upon a period drawing, was erected on September 4, 1861, just six weeks after the battle. After the Confederate Army moved from the area in 1862, the monument disappeared, and today its fate is unknown. A small stone on the battlefield is believed to be the original base for the monument.

Detail from "Battlefield of Manassas," 1861, showing the now lost Francis Bartow Monument. Manassas National Battlefield Park. (National Park Service)

Detail from "Battlefield of Manassas," 1861, showing the now lost Francis Bartow Monument. Manassas National Battlefield Park. (National Park Service)

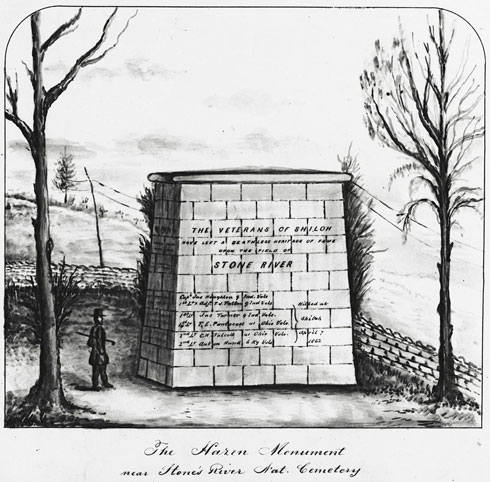

From December 31, 1862, through January 2, 1863, Union and Confederate forces clashed outside of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, in the Battle of Stones River, which resulted in a Union victory. Union General William Hazen's brigade, consisting of the 9th Indiana, 41st Ohio, 6th Kentucky, and 110th Illinois infantry regiments, was posted at the edge of the Round Forest astride the tracks of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad. On January 2, the brigade helped repel four Confederate attacks in fighting so vicious that afterward the soldiers nicknamed the location "Hell's Half-Acre." Later that year, members of the brigade erected a monument on the site to honor the fallen. Fabricated from limestone masonry, the Hazen's Brigade Monument is 10-square-foot block with a curved cornice, an unusual design for a Civil War monument. Forty-five soldiers were buried nearby. In 1864, stone cutters carved an inscription on the monument, including the names of 17 officers. Today, the monument is located in Stones River National Cemetery. For many years, the Hazen's Brigade Monument was considered the oldest extant Civil War monument. It is still the oldest Civil War monument in its original location.

After Lee's surrender at Appomattox, the federal government was faced with the fundamental task of locating and recovering the burials of Union soldiers scattered throughout the South. In the spring and summer of 1865, Army Officers worked to locate the remains of Union soldiers, but their efforts were piecemeal in the absence of firm policy. In response, Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs issued General Orders No. 65 in October 1865, which called upon officers to conduct a survey across the American landscape to identify the location of the remains of soldier dead, and provide recommendations for the disposition of remains. These orders became the core of the Union's burial policy, to inter the remains of every Union soldier within a national cemetery if possible. This was the most immediate and basic act of commemorating the Civil War dead.

In the mid-to-late 1860s, the federal government established national cemeteries, largely in the South. During this process, the War Department actively reinterred the recovered Union remains in the cemeteries and constructed other modest aspects of the sites. Permanent features of national cemeteries, including superintendent's lodges, enclosing walls and fences, and government-issued headstones were not fully realized until the next decade. National cemeteries were a natural setting to focus the nation's commemorative efforts, and especially to erect monuments to honor the fallen soldiers buried there. While a handful were dedicated during the late 1860s, it was not until the cemeteries were fully constructed and landscaped that monuments to the Union dead began to be donated and erected on a regular basis.

Drawing of Hazen Monument in Stones River National Cemetery from the "Report of Lt. Col. E.B. Whitman, Superintendent of National Cemeteries, Dept. of the Cumberland, 1869." (National Archives and Records Administration)

Drawing of Hazen Monument in Stones River National Cemetery from the "Report of Lt. Col. E.B. Whitman, Superintendent of National Cemeteries, Dept. of the Cumberland, 1869." (National Archives and Records Administration)

The former Confederate states were economically and socially devastated at the end of the war. During Reconstruction, the federal government removed the civilian governments in the southern states and put the U.S. Army in control. Lincoln's assassination, along with the postwar revelations of the poor treatment of Union prisoners, undermined any sympathetic Northern feelings toward the Confederacy. In this environment, efforts to memorialize the Confederate dead were met with skepticism and hostility on the part of the North. Immediately after the war, the federal government did not attempt to organize an effort to identify and mark the remains of the Confederate dead. Instead, local memorial groups and associations took on the responsibility of reinterring Confederates in private cemeteries. Of these groups, the highest profile may have been the Hollywood Memorial Association of the Ladies of Richmond, Virginia, which identified and located the remains of thousands of Confederate soldiers in and around the city and reinterred them at Hollywood Cemetery.

Civil War battlefields were also intuitive locations for groups to erect monuments and memorials. In the decades after the war, sections of the battlefields were preserved at Shiloh and Stones River, Tennessee; Antietam, Maryland; and the Wilderness, Virginia, among others. However, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania - the site of the bloodiest battle of the war - was the natural location for the first battlefield preservation efforts to crystallize. Nine months after the battle, while the Civil War was still raging, the Pennsylvania Legislature authorized the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA), a local organization, to:

…hold and preserve, the battle-grounds of Gettysburg…and by such perpetuation, and such memorial structures as a generous and patriotic people may aid to erect, to commemorate the heroic deeds, the struggles, and the triumphs of their brave defenders.

The GBMA began purchasing portions of the battlefield soon after.

Outside of national cemeteries and battlefields, monuments were erected in private cemeteries, and on public grounds such as statehouses, local courthouses, and parks. In private cemeteries, monuments were often dedicated to the soldiers buried therein. The monuments on state and local lands were often dedicated to the soldiers from that state or locality.

The advent of Decoration Day (later renamed Memorial Day) symbolized the national mood to honor the fallen Civil War dead; naturally, national cemeteries and the grave sites of fallen soldiers became the scenes of commemorative ceremonies. The exact origins of this national day of remembrance remain unclear, and the first observance is a matter of dispute. However, by early May 1868, John Logan, the Commander in Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a fraternal organization of Union veterans, issued General Orders (G.O.) No. 11. While not a military order, G.O. 11 designated May 30 as a national day of commemoration of the Union dead internally to the GAR. Early on, these commemorative efforts included processions to local cemeteries, prayers and hymns.

In the South, local efforts to commemorate the dead led to ceremonies on Confederate Memorial Day. The opaque origins of Memorial Day have led some to argue that the Northern holiday was adopted from the Confederate version. In the absence of a large fraternal organization such as the GAR to establish a specific date, many Southern states observed Confederate Memorial Day on different dates. This also reflects the local, grassroots nature of such commemorative efforts.

In some cases, these commemorations culminated in the erection of memorials. For example, the monumental pyramid erected in 1869 at Hollywood Cemetery was dedicated to the Confederate enlisted men buried in the cemetery.

The federal government constructed a small number of monuments at prisoner-of-war sites in the former Confederacy, such as the granite obelisk dedicated in 1876 to the unknown dead in Salisbury National Cemetery, North Carolina. But the vast majority of monuments in national cemeteries were patriotic gestures donated by state governments, regimental groups, or other military associations such as the GAR.

The mid-to-late 1870s were characterized by an increasing number of monuments erected to Union soldiers. On the Gettysburg battlefield, the rise in memorialization was symbolic of the increased attention of the country itself to reflect upon the war's meaning. The GAR of Pennsylvania erected the first monument outside of the cemetery, a marble tablet, in 1878. The following summer, the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry placed on the battlefield the first monument dedicated to a regiment.

By the late 1870s and early 1880s, national membership in the GAR was soaring. What started as a small organization in 1866 grew to a membership of 45,000 in 1879, and to 233,000 in 1884. By the 1880s, the GAR had grown into a powerful national organization, lobbying the federal government on issues important to Union veterans, including pension benefits for veterans and their dependants. After an intense GAR lobbying effort, in 1888 the federal government adopted Decoration Day as a national holiday for federal employees.

The GAR also engaged in many fundraising efforts for the carving and installation of monuments dedicated to Union veterans. In properties administered by NCA, the GAR donated monuments at the Albany Rural Cemetery Soldiers Lot, New York; and San Francisco, California, and Loudon Park (Baltimore), Maryland, national cemeteries.

Many GBMA members were also in the GAR. In the mid-1880s, the GBMA began making preparations for the 25th anniversary commemoration of the Gettysburg battle. In support of this effort, it was resolved that regimental monuments should be "placed at the location held by regiments in the line of battle." The ceremony took place on July 3–4, 1888, and included the dedication of 133 regimental monuments. Today, the regimental monuments at Gettysburg National Military Park contribute to its status as one of the most historically significant landscapes in the United States.

Confederate Monument, Finn's Point National Cemetery, 2005.

Confederate Monument, Finn's Point National Cemetery, 2005.

The 1880s were the advent of the great age of Civil War monuments. While no national inventory of Civil War monuments exists, a significant number were erected in properties currently administered by NCA, and can serve as a representative sample to illustrate the nationwide pattern of commemorative efforts. The number of monuments dedicated to the Union dead in cemeteries now overseen by NCA increased significantly in the 1880s, and peaked in the 1890s, then declining steadily from 1900–1930. Nationwide, it is likely that Civil War monument installation followed the same pattern.

Within this overall trend, from the 1890s until approximately 1920, many state legislatures in the North funded the installation of monuments in national cemeteries where large numbers of their dead were interred. For example, the state of Minnesota erected monuments in five national cemeteries: Jefferson Barracks (St. Louis), Missouri; Little Rock, Arkansas; Memphis and Nashville, Tennessee; and Andersonville, Georgia.

Southern commemorative efforts increased in the late 1880s and throughout the 1890s, in part as a result of the establishment of groups dedicated to honoring the Confederacy and the Confederate dead. The United Confederate Veterans (1889), United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC - 1894) and the Sons of Confederate Veterans (1896) were all founded during this period. Local chapters often raised money to sponsor monuments to be placed in public spaces. Confederate monuments were more frequently erected from the 1890s onward.

By the end of the 19th century, the national mood had begun to soften away from the remnant bitterness between the Union and the Confederacy. In part, the brief Spanish-American War of 1898 fostered nationalist feelings across the country. In 1906, Congress established the Commission to Mark the Remains of the Confederate Dead. Using this as a vehicle, the federal government erected a series of monuments dedicated to Confederate soldiers who died in former prisoner-of-war camps in Northern states. Monuments were erected in Point Lookout Confederate Cemetery (Ridge), Maryland; Finn's Point National Cemetery (Salem), New Jersey; Union Cemetery (Kansas City), Missouri, and Woodlawn Cemetery (Terre Haute), Indiana.

By 1920–1925, Civil War monuments dedicated to both sides of the conflict were erected less frequently as veterans aged and died, and as the nation's attention turned to commemorating 20th century conflicts. Still, the Civil War continues to resonate deeply with the American public, and periodically new monuments are erected. For example, in 1999, the African-American Civil War Memorial was dedicated in the U Street neighborhood of Washington, DC. A new monument to the U.S. Colored Troops was erected in Nashville National Cemetery in 2005, and throughout the 2000s the UDC installed monuments dedicated to the Confederate Dead at Mound City and Camp Butler (Springfield), national cemeteries, and at Rock Island Confederate Cemetery, all in Illinois, and at Confederate Stockade Cemetery (Sandusky), Ohio.

Conclusion

At the time August Bloedner carved the 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument, the Civil War had just started. Most of the major battles were still in the future, including Antietam, Gettysburg and Shiloh. The federal government had not established any national cemeteries, or even begun a comprehensive, organized effort to mark the remains of its fallen troops. In this context, the monument simply marked the remains of soldiers from the 32nd Indiana Infantry who fell during the Battle of Rowlett's Station.

There is a contrast between the patriotic American imagery of the carved frieze and the "foreign" German inscription which is emphasized by the fraktur-like script. In this sense the monument symbolizes the situation of German immigrants in the United States in the 1860s who lived in two worlds. The 13 soldiers whose names are inscribed on the monument enlisted, fought and died for their adopted country - even though none were native born, and even though they still spoke German as their primary language.

32nd Indiana Infantry Monument at the Frazier History Museum, 2010.

32nd Indiana Infantry Monument at the Frazier History Museum, 2010.

The 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument is one of a handful of monuments erected during the Civil War. After the war, the country was literally torn apart both politically and economically. During Reconstruction, the nation tried to repair itself while wresting with the seemingly intractable problem of welcoming the 11 seceded states back into the Union. By the late 1870s, the last federal troops withdrew from the South, marking the end of Reconstruction. In this national climate, efforts to commemorate the Civil War dead through the erection of monuments and memorials began in earnest, a reflection of the increasing public consciousness to memorialize military valor. Of the hundreds of monuments in metal and stone standing in cemeteries, battlefields, and parks dedicated to the soldiers of the bloodiest war in American history, the 32nd Indiana Infantry Monument is the first.